Australian Opals: Know Before You Buy

Did you know that Opal is the birthstone of October? To celebrate this month of opal, we would like to share with you a little information about this amazing gemstone, and why we are so passionate about it here at Giulians!

What is opal, and how is it formed?

Opal is a form of hydrated silicon dioxide (chemical formula SiO₂·nH₂O). Opal is formed in dessert-like areas, where the geology is rich in silica deposits – sedimentary rocks like limestone or sandstone – and there is strong seasonal rainfall followed by long hot and dry periods. During heavy rain, the water carries the silica from the rocks with it and creates a silica-rich solution which finds it’s way deep into the earth, below the water table. During the dry months, the sun dries out the earth causing the water table to evaporate and retreat, leaving microscopic spheres of silica behind. This process, repeated over millions of years, slowly creates layers of the silica spheres, and this is what forms opal.

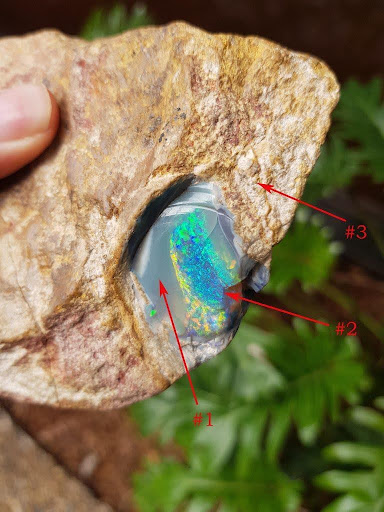

Not all the opal formed will show the spectral hues we all love – a lot of what forms is called common opal, which can be a non-descript bluish-black or milky white colour. The opal that shows the brilliant play-of-colour (or what many people refer to as ‘fire’) is known as precious opal. Most opals are cut into gems with a component of common opal or host rock still attached, as it plays an important role in the look and strength of the gemstone.

This is a large specimen of mostly common opal – with a small section of precious opal showing blue green play of colour.

Why is opal found in Australia?

The reason opal is found in Australia is due to the Great Artesian Basin. An artesian basin is an area where a body of groundwater is confined under the earth, held under pressure by surrounding layers of rock. The Great Artesian Basin is the largest and deepest artesian basin in the world, covering 23% of Australia and stretching 1,700,000 square kilometres below arid and semi-arid parts of Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory. It has a total volume of water of approximately 64,900 million megalitres.

The Great Artesian Basin was formed about 130 million years ago, by a sheet of quartz over a shelf underground. Rain ran off the mountains of the Great Dividing Range, creating rivers. The water on the eastern side ended up in the ocean while the water on the western side had no-where to go and just sat and sank into the earth. This process occurs every wet season, and has been occurring ever since the Dividing Range was formed (Over 300 million years ago) and heavy rain has come down. If you look at the opal fields in relation to the basin, it is little wonder why opal is mined in these locations.

Map of Australia, showing the Great Artesian Basin in light blue, in correlation the 3 major opal fields. (Tentotwo, Great Artesian Basin, added locations by ACoffey, CC BY-SA 3.0)

What causes the amazing colours seen in precious Opal?

The spectral colours seen in opal comes from the dispersion of white light through the layered spheres of silica. For this to occur, however, the layering and stacking of the spheres of silica need to be both uniform in size and perfectly structured. Without this structure, the result is common opal, or what we call potch in Australia.

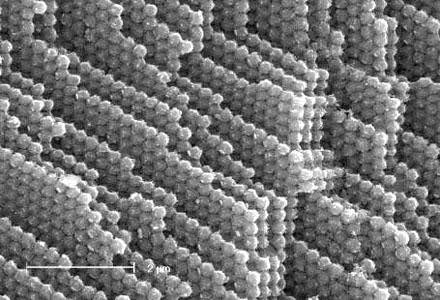

Scanning electron microscope imaging of the silica spheres of gem grade opal

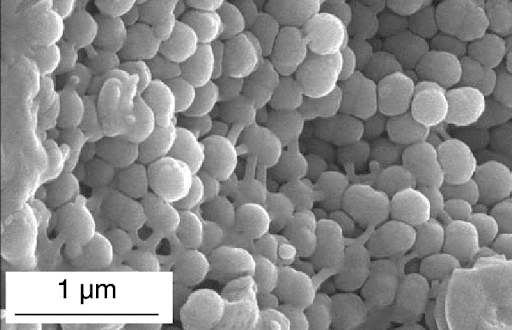

Scanning electron microscope image of common opal. Notice the irregular and non-unified structure.

The stacking and uniformity of the silica spheres is not the only factor involved. The size of the silica spheres determines the range of colour seen in the precious opal. Smaller clusters of stacked spheres will show blue-greens, while the larger spheres will show the rarer colour – red. The conditions opal is formed under generally wouldn’t allow for a lot of space, so the smaller spheres (and therefore the blue-green colours) are more commonly found.

Rare and bright reds, combined with dark coloured potch is said to be the ultimate in opal, referred to in the industry as ‘black on red’, and will be considered very valuable.

The best thing about the colours found in opal is the diversity. No other gemstone has such a variation of colour, pattern and combinations, so personal taste plays a major role in which opal appeals to you!

Black Opal – Lightning Ridge, New South Wales

The most valuable of Australia’s opal is Black opal. Black opal is found in sandstone, mined approximately 20 metres below the ground.

#1 Common Opal or Potch, #2 Precious Opal, #3 Sandstone.

Because it forms in sandstone, a relatively soft rock, it allowed for deeper deposits to form. Some of these deposits are called nobbies. A nobby is bulb shaped opal nodule found in clay which can be quite large or the size of a pea. They are tumbled to remove the sandstone, then ‘rubbed’ to allow the miner to look at the colour and quality. Nobbies are mostly mined in Lightning Ridge – which is why black opals are known for being cut into lovely high-domed cabochons. Other deposits of opal, like seam opal, occur in veins and bands and therefore yield thinner and more irregular shaped gems.

A nobby of black opal – which has been tumbled to remove the sandstone and rubbed to reveal the opal.

I thought black opals were supposed to be… black!

Many people who come to view our black opals often make this observation. The truth is quite the opposite! The potch found in Lightning Ridge is a darker body colour than that of white opal – and that is where black opal got its name. The darker the body colour, the better the contrast between the common and precious opal – resulting in more vivid and striking play-of-colour in the gemstone. The black opal potch can vary from inky-black through to very light grey – the light grey tones resulting in softer colours. The potch is almost always kept as part of the finished gemstone – to provide thickness, strength and colour depth. In thicker colour bands, black opal can be cut without its potch – and this is sometimes referred to as black crystal or jelly opal.

Boulder Opal – Quilpie, Queensland

First discovered on a station south of Quilpie in 1872, boulder opals are found in a belt stretching from Quilpie to Winton in Outback Queensland. Natural boulder opal is very unique. Unlike black opal, it is formed in an area where the geology is made up of ironstone. Ironstone is a dense sedimentary rock that formed in the Cretaceous period. Due to this density, the host rock was very unyielding, so the opal formed in cracks and fissures within the ironstone. These are referred to as veins, and they can vary in thickness from fine through to thick.

Because the majority of boulder opal veins are thin, the ironstone boulder is cut as part of the gemstone – giving the opal its name. Miners split the boulders through the veins, leaving the thin opal on the surface with the ironstone behind.

Due to the reddish brown to brown-black colour of the ironstone, the play-of-colour seen in boulder opal can be very similar to that of black opal. The natural ironstone makes up some of the carat weight, so boulder opals will generally cost less than a Black opal. You will also get more free-form and undulating shapes in boulder opal, as the miners have to follow the natural directions of the opal vein.

White Opal – Coober Pedy, South Australia

The name Coober Pedy is said to have evolved from a combination of two Aboriginal words meaning ”white man in hole”. Kupaka – meaning white man and Piti – meaning hole. White opal forms in limestone which, like sandstone, is a soft host rock allowing deeper deposits to form and the mining process more similar to black opal. The body tone of white opal is much paler, so the play-of-colour seen is more bright pastel hues. It is not uncommon for white opal to be cut without its potch which means the opal play-of-colour will be seen from the front and the back.

A rough piece of white opal – displaying a milky body colour with a little pastel fire.